A mariner is adrift at sea and his future looks bleak. He ponders how he will die: Lost in a storm? From dehydration? Or by the sea beast that taunts his tiny boat?

They call me Mito, Son of the Nasodranda, the short grey people. Stoum of the Isle of Irit, in the northern ice where the blackwings herald the coming of the naso. They call me Blackwing, after my hair – as black as my namesake.

Blackwings circle my ‘pooner.

I grip the gunwale. A grip that, by rights, should splinter wood and split my nails. Over its edge, everywhere I look. My grey features are reflected back at me in moon-silvered waters.

A blackwing rests upon the prow, and I know it too swift to be food.

The serpent circles beneath – waiting. Why?

It has destroyed Brinar’s Harvest, the barque I crewed. Forty souls, six ‘pooning boats, tackle, harpoons, lances, and try-pots for blubber boiling. Now a slick of wreckage. A smear of ship.

Not long after the sinking, I had rescued an onion-shaped bottle of rum that came bobbing along like a harbour master intent on fees. It tastes of the Humans who distilled it.

With rum and time come memories:

I remember the Harvest lurching aft, her forecastle erect as she pitched, block and tackle drumming in the leviathan’s approach, tolling fate rather than land’s approach. In a ship, land comes to you, as do monsters.

Down she slapped. All hands to their knees, some overboard. Human and Stoum peered over the gunwale. A shout. Another from the nest, sea dragon they call it – these Humans.

We (my tribe) call it naso.

Larboard, starboard, tentacles breached the water. Prayers … Human melodies over our Stoumish rhythms, Naso-naso – the old tongue. It came then. Bigger than I’ve ever seen, an axe swing to cleave the Harvest in two.

My furs are frozen this morning. Blackwings mob the prow. Me, too cold to startle them and they, too brazen to care. They want my eye-morsels.

‘You can’t have them.’

An empty line barrel, a mariner’s cap, a shattered harpoon haft, and me. Flotsam. A groan from the depths. The naso reminding me of its presence as it has done since the sinking.

Sometimes a fin-tip breaks the surface like a ghostship rising, black sail slicing the air. The seabirds take wing, circling. Sometimes the naso sprays this little ‘pooner. A tail slap testing my nerve.

Another shivering day. Third or fourth? A rum-soaked mind tallies time in bottles. This one is almost drained.

At it again, haunting me, the naso splashes and, this time by providence sends a smiling tide of flotsam my way.

I’m greedy for the canvas and splintered planks, but hope for rum. Instead, lashed to an oil barrel, I find a woman. Stoum.

I haul her up like a great limp fish, and lie her naked at the prow.

Now there are two.

Two mouths to feed. Two bodies to warm. Two folk to water.

I hide the rum.

Her grey face is bruised. Her plump body sagging. Her hair, like most Stoum (except for me) is ice white. Her scales are smooth and light, lighter than mine. She’s a mainlander perhaps.

A knock. A leviathan’s groan.

I’m at the gunwale peering into the deep.

‘Forget her,’ says the woman, startling me.

Her voice is strange, almost a blackwing’s croak. Dry and unused. She is alive then. There is water – water I shunned for a skinful of rum. The waterskin is uncorked and to her lips and declined in one swift motion.

‘You must drink,’ I tell her. She does not. Where are your clothes? ‘You were out there, all this time?’

‘Where else?’ she says. She eases herself up. ‘Why don’t you have some?’

I cork the waterskin and toss it in the ‘pooner. ‘Not thirsty,’ I say as I coax my rum from its hiding place.

‘Except for that?’ she says. She closes her eyes. Blackwings circle above, irritated by the trespasser in their spot. ‘What do you fear?’

The question is odd from a stranger. The frankness of a tired mind I suppose. No preamble, no introductions.

I drain the onion, toss it.

The bottle skulks away. Now a harbour master robbed of a fee.

‘Who are you, woman? I do not remember you from the Harvest.’

I take off my furs to drape over her.

‘Kind of you. Woman? Is that how you’d call me?’

‘I have no other name.’

‘Asil,’ she says, hand on heart. ‘Potter. You’re a ‘pooner? Beast slayer.’

She eyes the tooth around my neck. The Humans on the barque thought it meant such things.

‘Sign of a fisherman – in my tribe,’ I say.

‘The naso is not a fish.’

‘Hunting them pays better.’

‘More teeth for necklaces?’

I stop fiddling with the tooth.

‘This was a gift … from my father,’ I tell her.

‘For luck in the hunt?’

‘Not quite. But luck, yes. You’re not an islander.’

This is plain by her strange name, her clumsy and searching speech. As if she can’t quite grasp the words – Human words. We all speak their way now. Or perhaps it is the cold.

‘Not an islander,’ she repeats.

‘Rhodethå? Stoum home?’

‘… Yes,’ she says ‘You are an islander.’

‘Aye.’ Another Human word. I do not know Stoum, only Naso-naso.

A groan ripples up. The blackwings that had settled about the woman jostle into the air squawking.

‘Humans call that the devil’s speak,’ I say and nod to the birds. ‘Though I know not of what devils they mean.’

‘Huuumans? They owned the ship?’ she asks.

She is strange this woman, yet reminds me of Kizna, my sister. Round cheeks, a smile that traverses oceans.

‘Sorry,’ I say ‘I don’t remember seeing you onboard. We ‘pooners tend to stick together.’

She looks into the water just as a sail-fin breaks the waves.

‘You see me now. That is what counts.’

The blackwings seem torn to circle the spot where there is fin and where there is woman.

‘Do you wish revenge?’ she asks.

A good question, one circling my mind constantly squawking, If only for a harpoon and a barrel of line. ‘Revenge? No. The crew knew the risks.’

‘I do – want revenge for the dead. Judgment.’

‘Perhaps the naso is that judgement,’ I say.

Asil shifts beneath my furs. The boat creaks over a wave.

‘What makes you say this?’

‘My people, the Nasodranda, it means friends of the naso—’

‘Yet you hunt them.’

‘Yes’—it’s complicated—‘my people believe if the naso comes close to land, it is ready to die. Our people may take its body for the winter. One is usually enough for a year’s bounty.’

‘You believe this? You I mean, not your ’—she searches out the word—‘your tribe.’

Sometimes I’m not sure. Most times I don’t think. Most times I drink rum. Now that there is none, thoughts curse me. My fingers find the naso tooth about my neck and through it my father speaks.

‘You remind me of him,’ I say.

‘Him?’

‘Sorry. No, you are pretty. Strong-pretty … what I mean is, the way you talk in questions – like my father.’

‘This is a compliment?’

Yes. ‘A straight-talking man. Chief. He is angry with me. Has been for some time.’

‘Because you hunt the naso?’

My laugh hurts. A dry croak.

The blackwings perched about Asil think I’m talking to them and croak back.

‘The heralds, they like you,’ I say.

‘Heralds?’

‘Of the naso. Blackwings flock when one is near. Must be right beneath.’

I lean to the gunwale and peer through the waves.

‘What are you waiting for?’ I ask the sea.

The sea remains silent.

‘My father is angry,’ I continue. ‘Not so much for hunting naso, but doing so the Human way. Theirs is an efficient greed. At first, the lays were enough.’

‘And now?’

‘Lately, I have considered returning to my tribe, forsaking the ‘pooning lays. That coin is stained with too much blood. I see now. Our homes are brighter for the oil but it is a dark brightness. We’ve grain and nice-to-look-at things, our clothes are—we look like the Humans now.’

The boat rocks in those rumless thoughts.

Rum.

Empty bottles even when full, father would say. Emptiness to fill your gut with more emptiness.

‘I wish to speak no more,’ I tell her.

I take the ragged canvas and pretend it is fur.

I just want to sleep.

Asil says nothing.

The birds tuck their heads under their wings.

Knocking. The morning is knocking. I find my fur is empty of woman and Blackwings line the prow, bobbing and jeering at the sea. The knocking is there.

I scramble.

She’s drowned herself?

A barrel bobs up.

I snag it and heave the rope it is tied to, reeling in a harpoon gripped in Asil’s pale grey hands.

‘Are you mad?!’

‘You s-speared me,’ she gasps, smiling. ‘It was f-floating ‘neath the waves.’

Furs are over us. She is an ice slab I try to melt with my warmth.

‘You stubborn fool. You swim? With that beneath? It could swallow you whole,’ I whisper.

‘I could swallow this boat,’ she stutters.

Her words make no sense. She is stupid with cold.

‘Is this not what you wanted?’ she asks.

We stare at the harpoon. Such a small thing by comparison. If only the naso would show more of itself.

In the afternoon, a fin cuts through the waves and the naso bares its flank.

‘She mocks you. She presents herself.’

‘So sure it is a she?’ I say. Such strange behaviour for such a clever naso.

The boat rocks in its circling.

‘We know our own,’ Asil says with a glance at the harpoon gripped in my hand. ‘She’s right there.’

I block out the seabirds, breathe in, and arch my arm back. I hold my breath as I focus on the spot. The harpoon leaves me and slips into the deep with no splash nor fuss. I’m back at the bow, hugging my knees.

‘Why did you do that?’ Asil asks.

‘It was taunting me,’ I tell her.

‘The naso?’

‘No. The ‘poon. A toothpick. Useless,’ I say. Besides, the fight has gone from me. ‘It is a waiting game. Always has been. The naso, the cold, starvation, dehydration. The water is gone. We’ve nothing to eat.’

Squawk!

‘You are too fleet of wing,’ I say to the blackwings, then to her, ‘and how is it I never see you drink?’

‘You sleep. I drink,’ she says.

‘I think I’m losing my mind.’

Another day, or is it two? Stomach cramps for breakfast and more knocking. Asil’s furs are empty again. Another swim? She goes, despite my complaints, and surfaces with all sorts of flotsam.

Today, a bottle of rum.

Later, when we have warmed each other beneath our fur shelter, she asks me, ‘You don’t want it?’

The bottle sits there, glinting in the soft light of a clouding sky.

‘I could pour emptiness right in … for what? For drunkenness’s sake? What of you? I cannot leave you to frost and blackwings while I drift in rum. No. I’ve lost the taste.’

‘I have lost the taste too,’ she says.

Asil quits our warmth to swing the onion into the sea. We watch as the naso’s tail breaks the water, sweeping the bottle from the boat. We laugh. Yet, that fleeting relief is lost upon noting the horizon.

‘Storm. To the east.’ I lick a finger and test the air. ‘We’re being taken the other way,’ I say, with regret.

‘You want the storm?’

‘The water it will bring.’

Night, and my dreams are rain, yet I sup rum from sky. It is all I taste. Pouring. Stinging. Burning. I drown in a sea of firewater, gasping for wakefulness.

I lurch awake. Morning has broken and the squall too. Travelled against the wind, how? The ‘pooner is tossed and I straddle it with my knees, gripping the gunwales, drinking the sky. A sky alive with pulsing veins of light and pounding fists of sound.

‘Asil, come – drink!’ I shout against streaking lightning.

The prow is empty. A nest of nets and flotsam, nothing more. I’m to the gunwale in a heartbeat.

‘Asil!’

The water suddenly forms a shape. Not Asil, but a fin. A tail. It rises up like a hammer in the hands of a giant smithy, black against the lighting and slowly it comes down with a great slap spraying my already drenched body.

This is my death! In a storm. To a naso!

I could ask for a worse demise – and more deserved. She shunts the ‘pooner and I’m on my back, staring into the knifing rain. The boat creaks and moans a mourner’s wail under the laughter of wind.

I am as the dead.

We lay them in boats like this, loaded with scantness and sent out to the cleansing sea.

I close my eyes.

Dreams of the dead are monochrome.

Colour means life, and here there is none.

Fins, like tented sails, shield me. Tentacle arms grasp, smother, shelter. Rain, even here, in this death-dream. Out there, beyond the shroud of sleep – smothering fin-wings.

A peck jolts me to life. The blackwing squawks and flaps off, leaving blood to trickle from my forehead. I’m up in the ‘pooner. About me are barrels, pots, pans. All laid here and there. Little ponds of rainwater, Asil’s gifts. Things that should never, could never, float.

Asil is gone.

I stare abaft and out to sea.

How could this little boat weather such a tempest?

It cannot be.

How come I now stare east past the prow to Irit, Isle of Stoum?

After so many returns, why do I feel as though I am finally coming home?

THE END

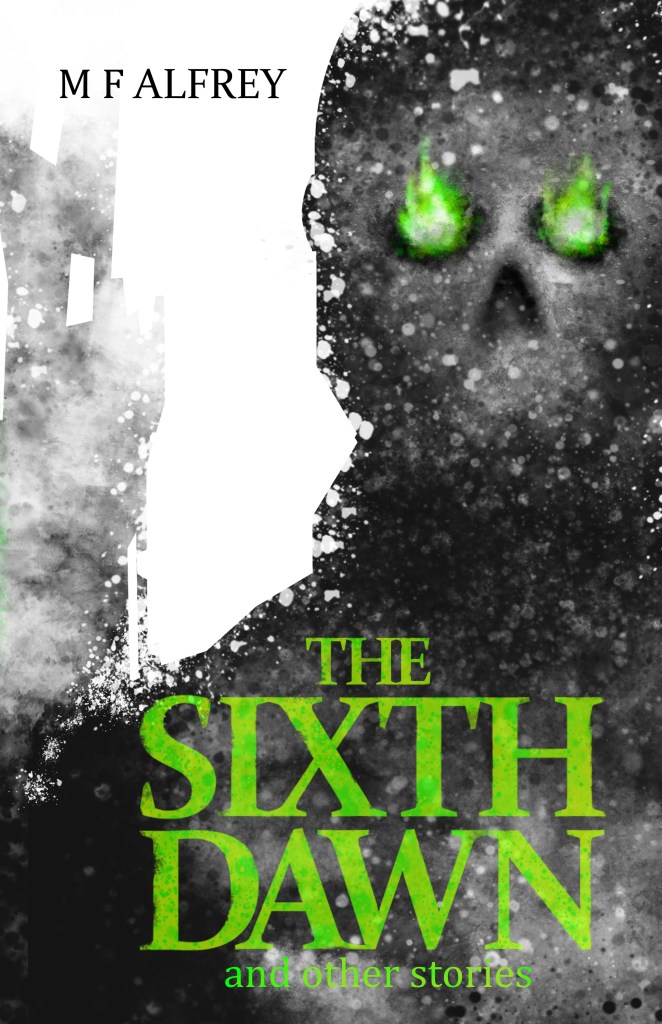

Like that? You may enjoy reading The Sixth Dawn, a collection of cosy-dark short stories from M F Alfrey’s fantasy world of Seodan.

#ad #PaidLink